Disability in literature has often been the brunt of the joke, forgotten, or not taken seriously. Dr. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson noticed this huge gap in the literary world and made it her mission to change that. Through her groundbreaking work, she has created new ways of thinking that challenge how disabilities are viewed, not as something to pity or fix, but as an essential part of the human experience that deserves respect, attention, and wonder.

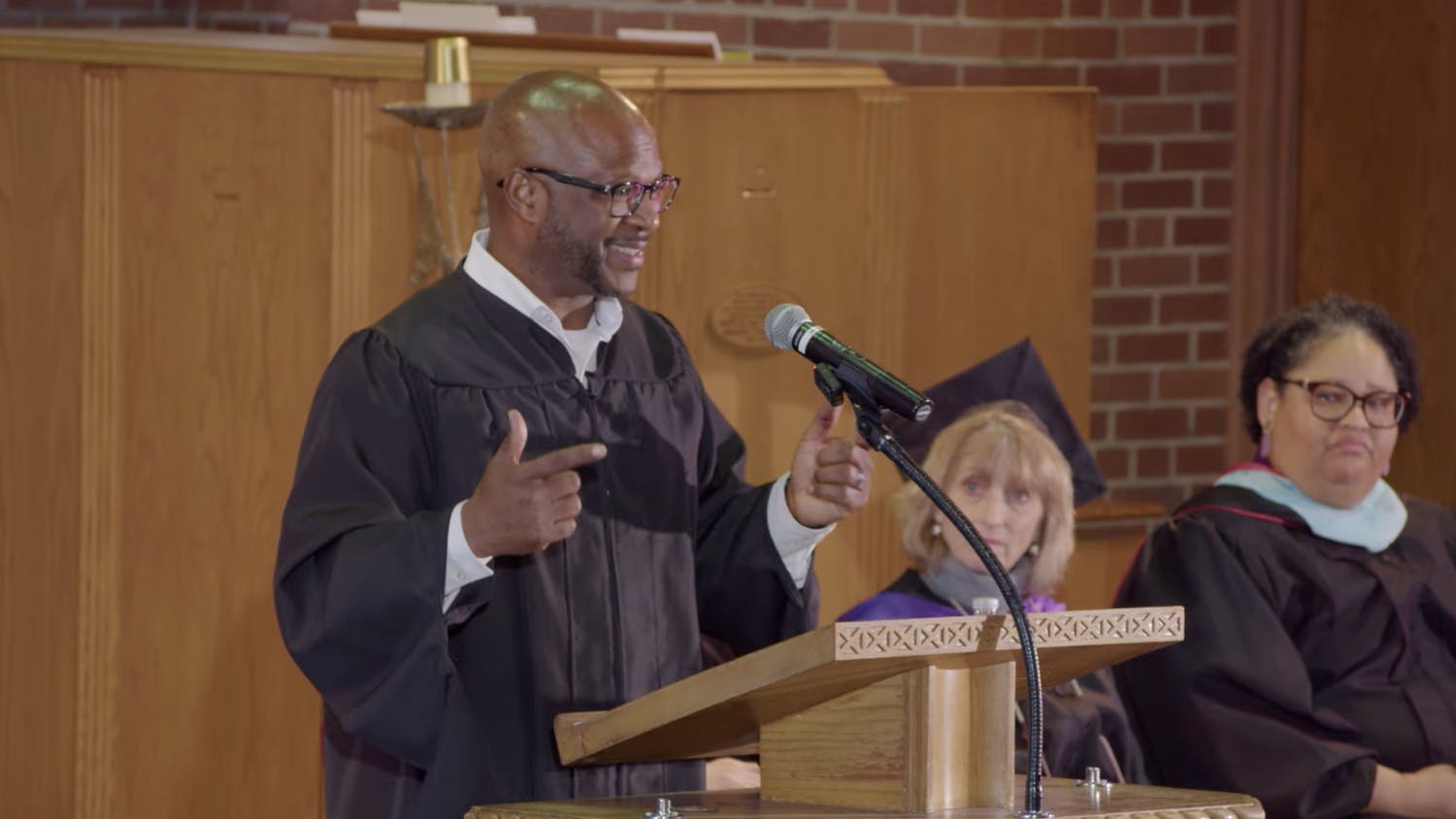

Garland-Thomson came to Wittenberg University on April 15th and 16th, a major name in the world of disability studies and health humanities. With a Ph.D.U in English and a Masters in Bioethics, Garland-Thomson has helped build an entire field that connects medicine with the humanities, and she’s made it her mission to make sure disabled people are seen, heard, and understood.

She’s also worked closely with Wittenberg English Professor, Dr. John Gulledge, back when they were both at Emory University, making it especially meaningful to have her here on campus.

During her visit, Garland-Thomson shared stories from her career and what led her to this work. She described herself as a “knowledge worker,” someone who always loved the humanities and arts, but never math. She started out teaching English but quickly realized that disability was largely missing from academic conversations. That realization sparked what became a lifelong commitment to creating space for disability in scholarship, literature, medicine, and everyday life.

In her recent talk at Wittenberg, titled A Call to Wonder, she challenged the audience to shift their perspective: instead of looking at disability with pity, fear, or distaste, she encouraged us to look at it with wonder. Wonder opens the door to understanding, creativity, and respect. It invites us to celebrate human diversity rather than trying to erase or "fix" it, she said.

Throughout her visit, she emphasized that disability is not rare or marginal; it is central to the human story. “Disability shapes lives and relationships,” she said. It’s something that touches every family and community, not just something hidden away in clinics or medical textbooks. Her work looks at how disability is represented in literature and uses her bioethics background to open conversations with scientists and doctors. She wants to reach everyone, not just academics, and shift the focus from stats and diagnoses to real people and their lived experiences.

A major part of her message involved rethinking design. Instead of forcing people to adapt to a rigid environment, disability design shapes environments to fit humans. It’s about creating a world where all kinds of bodies and minds can thrive, not just survive.

Garland-Thomson emphasized the importance of having diagnostic tools and narratives available. For many, getting a diagnosis isn’t about being labeled; it’s about having language to understand a new or shifting identity. Stories, not just clinical definitions, help people process and share their experiences. And through the humanities, we learn to see people as full beings, not just patients or case studies.

Her visit to Wittenberg was more than a lecture, it was a powerful invitation to rethink how we understand health, difference, and care. And more than anything, it was a call to bring disability out of the clinic and into the center of our shared stories.